Sweet Home

Sweet Home

Sweet Home is a Famicom horror RPG released in tandem with the horror film of the same name directed by Kiyoshi Kurasawa. The game was never localized, likely because it’s the most gruesome NES game I’ve ever seen. It is only available in English by fan translation and can only be purchased second-hand or as a repro, thereby passing Ren’s Justifiable Piracy test.

Sweet Home is the grandmother of the survival horror genre, heavily influencing Resident Evil and, in turn, games like Parasite Eve, Bioshock, and Corpse Party. It tells the story of a group of documentary filmmakers who visit an abandoned mansion that once belonged to the artist Ichiro Mamiya in search of his lost frescos, which are rumored to be hidden inside. Obviously, something goes wrong. As the documentary crew explores the mansion they can piece together the stories of those who came before through letters and bloody messages. The mansion seemingly has a will of its own. Chandeliers fall, chairs attack, and the inhabitants are extremely territorial. The game utilizes elements that have become staples of the survival horror genre: opening door sequences to build suspense, limited inventory, limited healing items, and exposition through found letters. Throw in a little permadeath, dead children, and legitimately creepy 8-bit shit and you’ve got a recipe for an excellent game.

Sweet Home was originally translated by Gaijin Productions and Suicidal Translations. As we all know, NES fan translations are the Lord’s work, and this one took over year. After I played through the game I learned The Siege and JMN released an updated translation in early 2017. The Siege has a lot to say about the original translation and feels that the quality of it has made the game unnecessarily difficult for English speakers.

Whichever translation you choose, I highly recommend this game. Ever since Corpse Party I’ve been looking for “more of that” and though this is an RPG and has less story content it scratched the itch. There’s lots of cool stuff in the game. The level design is excellent, the unfolding story is engaging, and I really enjoyed it.

I kind of want to do a Let’s Play, but I also kind of… don’t. Partly because Miketopus has done a written LP and there are at least 4 video LPs. I don’t think anyone has done the new translation yet. A compromise might be a more streamlined article that focuses on elements that I find interesting and less on walking through the entire game.

Sweet Home Part II: On Permadeath and Friendship

This is the first of a series of articles in which I won’t shut up about Sweet Home. For this one, I’d like to talk about Sweet Home’s chief weakness, which is the way it handles the crew as characters, and how two game mechanics work to make up for it.

Sweet Home’s playable characters are a documentary crew of five people who have the odd distinction of being interchangeable within the story but unique in terms of gameplay. Each possesses a special item than cannot be swapped out.

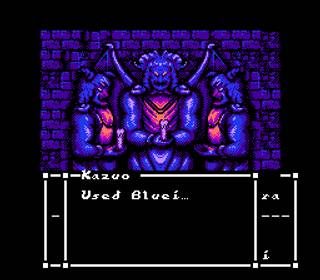

- Kazuo, who is either a smoker or a pyromaniac, has a lighter that can burn rope or be used as a weapon.

- Akiko carries a first aid kit, which can cure status ailments.

- Asuka, who is apparently a restoration expert, carries a vacuum which can clean up broken glass and dust. Sadly, it cannot be used as a weapon, which is clearly an oversight.

- Taro is the cameraman. In battle the camera can deliver damage light-sensitive enemies.

- Emi carries a key that for some reason works in half the locks in the mansion.

Sweet Home doesn’t attempt to explain who these characters are. This is probably because the game assumes the player is familiar with the movie the game is based on, this trailer shows the two marketed side-by-side. The player can name Kazuo, which seems a little strange since he’s a named character in the source material, but it makes sense if you consider that we don’t ever really learn anything about Kazuo and his name isn’t particularly important. He’s essentially a blank slate. Well, a blank slate with a lighter, which I’ll get to in a moment.

The introduction provides us with the only character-unique dialogue in the game. Any other time dialogue is spoken by the crew, it is delivered by the lead character. So while the game has 5 endings depending on how many crew members survive, the endings are only based on the number of crew left and not which crew members survived. This is a bit disappointing.

I think they prioritized other things and skimped on the crew’s characterization for two reasons. The first, again, is this game is a movie tie-in and players ostensibly knew the details. Secondly, two of the gameplay mechanics that make Sweet Home unique are mechanics that by their nature build a relationship between the player and the characters: permadeath and specialty items.

If death matters, the player will go to extra lengths to preserve a character’s life. If Emi dies, it means something. From a gameplay perspective, you need to find a replacement manor key, and if you haven’t progressed far enough you’ll be stuck in an unbeatable playthrough. But it also means EMI DIES. There’s one less living person in the mansion. Emi, who always helpfully scurried out front to unlock doors, is gone. She’s gone. FOR-EV-ER, leaving nothing but a cool death cinematic and a flickering sprite in her wake.

These are the people you crawled around in a blood-drenched basement with. We broke boulders together. We extinguished fires. We had oddly engaging conversations with severed torsos. If that doesn’t create a bond, I don’t know what does.

The player must interact with all of these characters because their special items are required to overcome the mansion’s various puzzles and obstacles. There are replacement items later in the game (matches, pills, the broom, a camera, and the wire), but using these takes up valuable inventory space. So it isn’t as simple as replacing a lost character with an item.

Welcome to inventory management hell. Each character has a special item, two item slots, and one slot for a weapon. Managing this limited inventory requires planning, forward thinking, and a good memory. When a character dies, you lose their inventory space, their special item, a space in your current inventory that will need to be used for a replacement item, and your battle and exploratory capabilities are reduced by one. By the time you get down to two characters, Mamiya mansion is going to be a much more sinister place.

Since each character is mechanically useful, and will be used regularly by most players, they begin to develop personalities based on the player’s gameplay style. In my game, Asuka is a vacuum-wielding badass who forges ahead as the leader of the main exploratory party and smashes enemies with a mallet. Taro is the guy who gets sent into rooms alone to “see what’s in there” because as a cameraman he has more limited utility. Akiko is the one who constantly has to save the crew’s bacon when they all get poisoned, frozen, or cursed. Asuka and Akiko make out sometimes but that’s neither here nor there.

Players do get attached to these characters, in spite of the lack of writing for them. The bulk of the game’s writing focuses on the Mamiyas, and without crew backstories the mystery and current situation take center stage in the narrative.

Sweet Home Part III: Cinematic Influence

Sweet Home nods to its cinematic inspiration while making excellent use of limited resources. Some of these visual ideas have had a lasting impact on the survival horror genre.

An investigation team searches for Mamiya Ichirou’s fresco… But it lies within the haunted Mamiya manor…

The game opens with a long shot of the mansion, establishing a sense of place and isolation.

This is the first instance of the cool door opening animation that we will see throughout the game whenever doors are unlocked. Opening-door animations would later famously be utilized by the Resident Evil series. Yep, it started here, folks. In later games this technique will be used to mask loading times, but in Sweet Home the animation is purely to build suspense.

Akiko: Let’s go! Prep the camera.

Asuka: Good, we’re all here. Somewhere in this mansion is Mamiya’s fresco, I’m sure. The fresco used a special tech–

Taro: What the?

Emi: Wa!

The front door slams shut and the room begins to shake and the ceiling collapses, blocking the doorway with rubble. Then, Lady Mamiya arrives. We don’t know anything about her yet, but it’s immediately clear something terrible has happened here. This room is characteristic of design throughout the game. It’s a small space surrounded by black. Many of the rooms will be tightly designed, often connected by winding hallways.

Asuka: The exit!

Lady Mamiya: Fools! Those who defile my home shall feel my wrath!!

She vanishes without giving us the deets. Assume the worst.

Emi: What’s going on?!

Taro: We have to escape!

Kazuo: There has to be another exit. We better search the mansion.

Kazuo: Also remember we each have our own tools.

This marks the end of unique dialogue for the crew.

The player how has control of Kazuo, who can reassure the rest of the team. It’s hard to tell if they’re all in shock or if getting locked inside a haunted mansion is just another typical day at Kazuo Industries. Remember how I talked about the crew’s lack of personality?

Kazuo: Asuka, don’t worry.

Asuka: Thanks.Kazuo: Akiko, don’t worry.

Akiko: Okay…Kazuo: Taro, don’t worry.

Taro: Alright.Kazuo: Emi, don’t worry.

Emi: Okay.

Stimulating stuff. Initiating conversation throughout the game results in the lead character providing a reminder about their special item, nothing more. It seems like a missed opportunity, but the game wants us to focus on the mansion and the Mamiyas. Fortunately, letters and messages will fill in the mansion’s backstory, and the entities we encounter in the mansion will have plenty to say.

Before I get into the epistolary storytelling, I want to take a moment to admire the game’s level design. The mansion layout is pretty amazing. The game requires backtracking (potentially a lot, if you have a bad memory or don’t manage your inventory well) and the developers have made the loops as painless as possible. Many of the maps are compact, and the efficient use of space lends a sense of claustrophobia. Opening locked doors with special keys often leads to aha! moments, because the layout makes spacial sense and is well-designed. I haven’t mapped out the screens, but I would not be surprised if they fit perfectly.

Dark hallways are lit by lightning, create a tense atmosphere.

Occasionally the crew discovers reminders of the people who lived here. The tile designer has made a point of giving each level of the mansion a unique feel. A lot of color is being used, and the palette choice keeps things visually interesting while maintaining the derelict vibe.

Environment puzzles lead to a custom scene that can be examined and interacted with up close. This allows close and long shots as well as more complex animations. Here’s an example of a puzzle involving two different knight statues. It’s an effective way to break up the gameplay and the visuals.